Published by InSight+ on 22 April 2024: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2024/15/who-pays-the-price-for-new-zealands-tobacco-backflip/

Repealing the smokefree Act in Aotearoa New Zealand preserves the tobacco excise as a revenue stream for the country’s government but also benefits the tobacco industry.

Against strong recommendations from Māori organisations and global public health authorities, on 28 February, the incoming Aotearoa New Zealand coalition government repealed the Smokefree Environments and Regulated Products (Smoked Tobacco) Amendment Act 2020 (the smokefree Act) (here).

This world-first legislation, passed in December 2022 by the previous government, aimed to achieve a “tobacco endgame” by rapidly reducing smoking rates to minimum levels (< 5%) for all population groups (both Māori and non-Māori). The legislation was the result of decades of Māori leadership and the work of generations of tobacco-control researchers and advocates in Aotearoa New Zealand and globally.

It included three key strategies:

- reducing the nicotine content of tobacco products to non-addictive levels (ie, denicotinisation);

- a 90% reduction in the number of tobacco retailers; and

- creating a “smokefree generation” by making it illegal to sell cigarettes to people born after 2008.

Our modelling of the potential health impacts of the smokefree Act showed that it was likely to deliver large health benefits to the population and substantially reduce the all-cause mortality gap between Māori and non-Māori (here).

To justify repealing the smokefreeAct, the incoming Minister of Finance pointed to its negative impact on the government’s budget, specifically the need to preserve tobacco excise as a revenue stream (NZ$ 1.67 billion in the 2022–23 financial year, about US$1 billion, or 1.5% of total taxation revenue) to fund income tax-cut promises made during the electoral campaign to middle and high income earners (here).

In our recent modelling study, we evaluated the potential economic effects of the combined tobacco endgame strategies included in the smokefree Act on government revenue and expenditure, and overall citizen income. Our analysis estimated that the rapid falls in smoking prevalence from implementing the smokefree Act, compared with business as usual, would generate substantial economic benefits for citizens (eg, US$22.4 billion less cumulative expenditure by citizens on tobacco by 2040 had the legislation been implemented in 2023) but $10.3 billion less cumulative tobacco excise tax revenue to government.

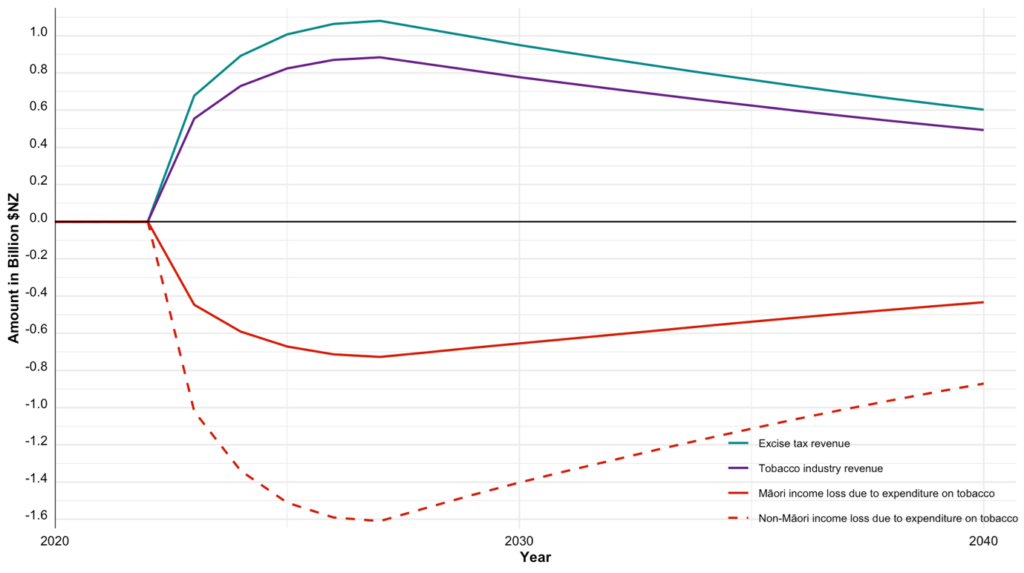

Figure 1 presents an extension to this analysis, showing the ultimate economic winners and losers resulting from the government’s decision. We estimated the annual increases in tobacco industry revenue, revenue to government from tobacco excise, and loss in disposable income for citizens as a result of expenditure on tobacco for Māori (17% of total population) and non-Māori.

Note: Amounts in 2021 New Zealand dollars with 3% annual discount rate. Tobacco industry is defined as wholesale, distribution and retail. Disaggregated estimates for Māori and non-Māori generated with our existing integrated epidemiological and economic model (methodological details here and here). Yearly tobacco industry revenue = yearly tobacco excise revenue (here) x ((1 – proportion of tobacco excise)/proportion of tobacco excise) (here). Annual projections estimated in the model as the difference between a counterfactual scenario in which the smokefree legislation remains in place and business as usual under which the legislation is repealed.

Repealing the smokefree Act would generate NZ$12.4 billion (95% uncertainty interval [UI], 9.9–14.7) in cumulative revenue for the tobacco industry by 2040, compared with a scenario in which the legislation remains in place. Approximately a third of that revenue (NZ$3.9 billion; 95% UI, 3.1–4.6) will be a transfer coming from the disposable income of Māori citizens.

High taxation of tobacco products (and subsequent government excise revenue) is one of the most effective policies to reduce smoking prevalence (here). It is also a progressive tobacco control strategy, as people on lower incomes, who often experience higher smoking rates, are more responsive to high cigarette prices — although for smokers who keep smoking, and do not reduce per day cigarette consumption, there is a high impact on disposable income.

Repealing thesmokefree Act preserves tobacco excise as a revenue stream for government but also benefits the tobacco industry by protecting the revenue it generates from selling smoked cigarettes to the Aotearoa New Zealand population. These benefits occur particularly at the expense of Māori who per capita contribute 2.3 times as much revenue from tobacco to both government and the tobacco industry. Given that people who smoke have on average lower incomes than those who don’t smoke (here), and Māori on average have lower income than non-Māori (here), repealing this legislation is a regressive way to pay for tobacco industry profits and the tax cuts planned by the new government.

The body of research informing the smokefree Act in Aotearoa New Zealand highlights the health, economic and equity gains that can arise from ambitious tobacco policy (and the lost opportunity if such policy is not pursued) (here and here). Achieving these gains takes strong leadership of civil society and governments. Moreover, from an economic perspective, beyond election cycles, dramatically reducing tobacco smoking makes sense because of the public health gains and consequent increased workforce productivity (here and here).

The Aotearoa New Zealand Government’s decision to repeal an carefully designed legislation, supported by tobacco experts globally and a large majority of the Aotearoa New Zealand population (here), has been described as an act of “public health vandalism” (here). Such a decision highlights how political short-termism and a lack of holistic thinking by governments can impede public health progress to the detriment of the health and economic wellbeing of the population.

Dr Driss Ait Ouakrim is a Senior Research Fellow at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Ms Samantha Howe is a PhD candidate at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Dr Tim Wilson is a Research Fellow at the Population Interventions Unit at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Professor Coral Gartner is a Director of the Centre for Research Excellence for Achieving the Tobacco Endgame at the School of Public Health at the University of Queensland.

Professor Tony Blakely is a Head of the Population Interventions Unit at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

This project was supported by funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT1198301).